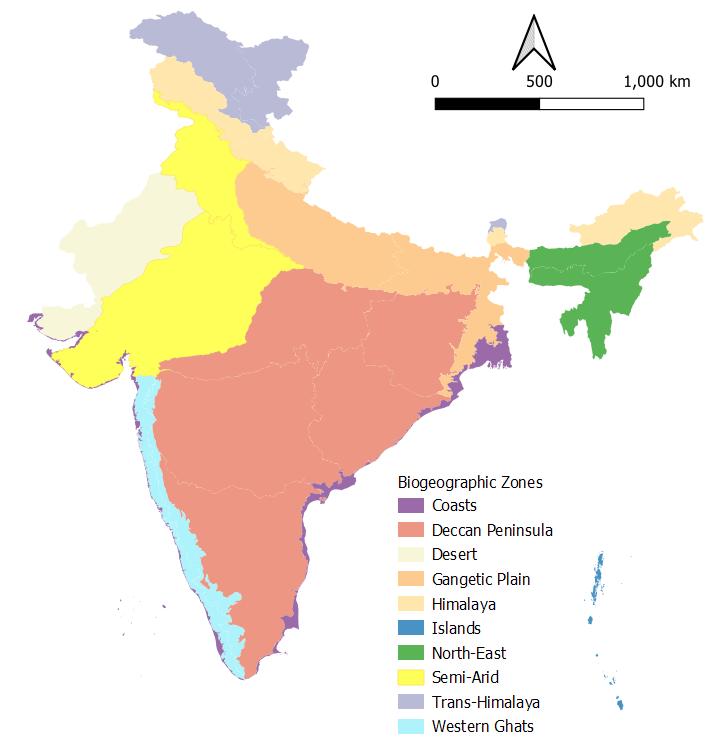

Biogeography concerns the patterns of geographic distribution of species and the processes that give rise to those distributions. Such processes include the movement the of tectonic plates (e.g., India’s separation from the ancient continent of Gondwanaland ~130 million years ago, Tandon et al. 2014), changes in climate over geological time (e.g., the establishment of the Indian monsoon 10-8 million years ago, Singhvi and Krishnan 2014), evolution of taxonomic groups (e.g., the ferrying of the ancestor of Asian dipterocarps from Gondwanaland to present-day Asia by the Indian landmass, and the diversification and spread of dipterocarps across South and Southeast Asia, Ghazoul 2016), and present climatic and geographic conditions (e.g., the present rainfall and temperature regimes that favour the presence of dipterocarp-bearing forests in India such as tropical evergreen forests and tropical dry deciduous forests). A biogeographic zone is a geographical region with a shared biotic composition that differs, on average, from other biogeographic zones. India has been classified into 10 biogeographic zones (Figure 1) and further sub-divided into 27 biogeographic provinces (Rodgers and Panwar 1988, Singh and Kushwaha, 2008): |

|

Figure 1. Biographical regions of India as defined by Rodgers and Panwar (1988). |

1) Trans-Himalaya: A cold and arid zone to the north of the Great Himalayan range and occurring between 4500 m and 6000 m above sea level. Its biogeographic provinces are Ladakh Mountains, Tibetan Plateau, and Sikkim. |

|

Figure 2. Sheep grazing in a grassland in Suru Valley, Ladakh. |

2) Himalaya: The highest mountain chain in the world. Its 2400 km-long expanse spans tropical, subtropical, subalpine, and alpine ecosystems. Its biogeographic provinces are North West Himalaya, West Himalaya, Central Himalaya, and East Himalaya. |

|

Figure 3. Temperate broadleaf forest near Mandal, Uttarakhand. |

3) Desert: Hot and dry in summer and cold in winter, desert ecosystems are dominated by scrub and grassland vegetation types. Its biogeographic provinces are Thar and Katchchh. |

|

Figure 4. Thorn scrub in Desert National Park, Rajasthan. |

4) Semi-arid: A transition zone between desert and denser forests consisting largely of thorn forests and savannahs. Its biogeographic provinces are Punjab plains and Gujarat and Rajputana. |

|

Figure 5. Savannah in Gir Wildlife Sanctuary, Gujarat. |

5) Western Ghats: A global biodiversity hotspot consisting of plains and mountains with peaks 800 m – 1500 m above sea level on average. Spans a large variety of vegetation types from tropical evergreen forests to tropical dry thorn forests to montane grasslands. Its biogeographic provinces are Malabar Plains and Mountains. |

|

Figure 6. Tropical dry deciduous forest in Mudumalai National Park, Tamil Nadu. |

6) Deccan Peninsula: A semi-arid region lying in the rain shadow of the Western Ghats. Contains a mix of teak and sal bearing tropical forests. Its biogeographic provinces are Central Highlands, Chotanagpur, Eastern Highlands, Central Plateau, and Deccan South. |

|

Figure 7. Tropical moist deciduous forest with sal (Shorea robusta) in Phen Wildlife Sanctuary, Madhya Pradesh. |

7) Gangetic Plains: Fertile plains in the Himalayan foothills that are largely populated today. Vegetation types include dry and moist deciduous forests. Its biogeographic provinces are Upper and Lower Gangetic Plains. |

|

Figure 8. Sal-bearing dry deciduous forest abutting a tributary of the Ganges near Rajaji Tiger Reserve, Uttarakhand. |

8) Coasts: India’s ~8000 km long coastline spans a range of terrestrial and aquatic ecosystems including forests (tropical dry evergreen and mangrove). Its biogeographic provinces are East Coast, West Coast and Lakshadweep. |

|

Figure 9. Restored tropical dry evergreen forest at Pitchandikulam Forest, Tamil Nadu. |

9) North-East: Includes the plains and non-Himalayan hill ranges of north-eastern India spanning a range of lowland and montane vegetation types. Its biogeographic provinces are Brahmaputra Valley and North East Hills. |

|

Figure 10. Indian rhinoceros in a swampy grassland in Kaziranga National Park, Assam. |

10) Islands: Consisting of nearly 600 islands, the islands are largely covered by tropical forests including evergreen, littoral, and mangrove forests. Its biogeographic provinces are Andamans and Nicobars. |

|

Figure 11. Tropical evergreen forest in Mt Harriet National Park, Andaman and Nicobar Islands. |

A given vegetation type that is found in different biogeographic zones will typically have different plant assemblages. For instance, tropical evergreen forests are found in the Western Ghats, Northeast, and Islands are physiognomically and structurally similar but have distinct plant assemblages due to their differing biogeographic associations -- even when they share contemporary climatic conditions. |

References |

GHAZOUL, J. 2016. Dipterocarp biology, ecology, and conservation. Oxford University Press. 329 pp. |

RODGERS, W. A. and PANWAR, H. S. 1988. Planning a wildlife protected area network in India. |

SINGH, J. S. and KUSHWAHA, S. P. S. 2008. Forest biodiversity and its conservation in India. International Forestry Review 10:292–304. |

SINGHVI, A. K. and KRISHNAN, R. 2014. Past and the present climate of India. Pp. 15–23 in Kale, V. S. (ed.). Landscapes and Landforms of India. Springer Netherlands, Dordrecht. |

TANDON, S. K., CHAKRABORTY, P. P. and SINGH, V. 2014. Geological and tectonic framework of India: Providing context to geomorphologic development. Pp. 3–14 in Kale, V. S. (ed.). Landscapes and Landforms of India. Springer Netherlands, Dordrecht. |

Endnotes |

The information on Biogeographic zones of India was authored by SANDEEP PULLA. |